Complainant has right to be heard at every stage of criminal trial, including revision-Said Delhi High Court

VLS finance ltd vs state nct of delhi CRLMC 8758/23 24/05/24 [ DELHI HIGH COURT ]

Section 482 CRPC Sections 406, 409, 420, 467, 468, 471 and 477A IPC Denial of impleadment and right to be heard Challenging Trial court’s order framing charges against the accused – Petitioner alleges that the accused approached them with a proposal to invest in a hotel project, misrepresented their financial capacity, and defrauded the petitioner of substantial amounts through false assurances and forged documents –

Plea that as the complainant/victim, they have a right to be heard at every. stage of criminal proceedings, including revision petitions – Held, petitioner, being the victim, has an independent right to be heard in the Revision Petitions, particularly because these petitions seek the culmination of criminal proceedings that could affect the petitioner – Therefore, it is correct not to implead the petitioner as a party to the Revision Petitions

Plea that as the complainant/victim, they have a right to be heard at every. stage of criminal proceedings, including revision petitions – Held, petitioner, being the victim, has an independent right to be heard in the Revision Petitions, particularly because these petitions seek the culmination of criminal proceedings that could affect the petitioner – Therefore, it is correct not to implead the petitioner as a party to the Revision Petitions

– However, the Court found that restricting the petitioner to only assisting through the APP was not appropriate – Petitioner should be afforded a fair and reasonable opportunity to be heard directly in the Revision Petitions – This includes the right to file written submissions – ASJ is directed to grant the petitioner a fair and reasonable opportunity to be heard in the Revision Petitions. [Paras 72, 73, 79 and 80]

– However, the Court found that restricting the petitioner to only assisting through the APP was not appropriate – Petitioner should be afforded a fair and reasonable opportunity to be heard directly in the Revision Petitions – This includes the right to file written submissions – ASJ is directed to grant the petitioner a fair and reasonable opportunity to be heard in the Revision Petitions. [Paras 72, 73, 79 and 80]

To read the judgment click here

Delhi high court Judgement The Law Literates

All rights reserved (Adv Vaibhav Tomar )

Evidence Act Section 106 Section 302 IPC Murder of own four month child — Bail – The petitioner is accused of murdering his four-month-old child during a quarrel with his wife

CORAM:

HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE VIKAS MAHAJAN

Ravi Rai vs STATE of Delhi BA 1725/23 08/04/24 [ DELHI HIGH COURT ]

Evidence Act Section 106 Section 302 IPC Murder of own four month child — Bail – The petitioner is accused of murdering his four-month-old child during a quarrel with his wife – The main issue is whether the petitioner should be granted bail considering the testimonies of the prosecution witnesses – The petitioner argues that the prosecution witnesses, including his wife, did not support the prosecution’s case, and he has been in custody for over two years without any criminal record or flight risk –

The prosecution contends that the wife did not support the case due to being the petitioner’s wife and suggests the burden of proof lies with the petitioner under Section 106 of the Evidence Act – The court granted bail to the petitioner based on the lack of support from prosecution witnesses and the prolonged custody without trial conclusion in sight – The court reasoned that the prosecution must prove the accused’s guilt beyond reasonable doubt before the burden shifts to the accused to explain facts within their knowledge – The court cited precedents stating that Section 106 of the Evidence Act does not automatically shift the burden of proof to the accused.

– The petitioner was granted bail with specific conditions, and the observations made are solely for the purpose of this bail application, not affecting the trial’s merits

To read the judgment click here

RAVI RAI versus STATE (GOVT. OF NCT OF DELHI) The Law Literates Judgment

All rights reserved (Vaibhav Tomar Adv)

Delhi High Court Issues Directions To Family Courts For Dissolution Of Muslim Marriage On Basis Of Talaq Nama, Mubarat Agreement, Etc. – The Law Literates

Delhi High Court Issues Directions To Family Courts For Dissolution Of Muslim Marriage On Basis Of Talaq Nama, Mubarat Agreement, Etc.

Relevant Paras

12. In the present case, we find that both parties had filed a joint petition before the leaned Family Court seeking a declaration that their marriage stood dissolved through Mubaraat on 24.01.2020 as per the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937. In support of their plea, the parties have relied on the Mubaraat agreement dated 24.01.2020 wherein it had been specifically recorded that the marriage between the parties stood dissolved by the mode of Mubaraat which is one of the accepted modes of divorce under the Muslim Personal Law. The fact that Mubaraat, wherein the marriage is dissolved with the consent of the parties is a recognised mode of dissolution of marriage under the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937, was duly noted by the Apex Court in paragraph nos.3 & 4 of its majority decision in Shayara Bano (supra). The said paragraphs

read as under:-

“3. The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937 (hereinafter referred to as “the 1937 Act”) was enacted to put an end to the unholy, oppressive and discriminatory customs and usages in the Muslim

community. [ “Statement of Objects and ReasonsFor

several years past it has been the cherished desire of the Muslims of British India that customary law should in no case take the place of Muslim Personal Law. The matter has been repeatedly agitated in the press as well as on the platform. The Jamiat-ul-Ulema-i-Hind, the greatest Moslem religious body has supported the demand and invited the attention of all concerned to the urgent necessity of introducing a measure to this effect. Customary law is a misnomer inasmuch as it has not any sound basis to stand upon and is very much liable to frequent changes and cannot be expected to attain at any time in the future that certainty and definiteness which must be the characteristic of all laws. The status of Muslim women under the so-called customary law is simply disgraceful. All the Muslim Women

Organisations have therefore condemned the customary law as it adversely affects their rights. They demand that the Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) should be made applicable to them. The introduction of Muslim Personal Law will automatically raise them to the position to which they are naturally entitled. In addition to this present measure, if enacted, would have very salutary effect on society because

it would ensure certainty and definiteness in the mutual rights and obligations of the public. Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) exists in the form of a veritable code and is too well known to admit of any doubt or to entail any great labour in the shape of research, which is the chief feature of customary law.”(emphasis supplied)] Section 2 is most relevant in the face of the present controversy:

“2. Application of Personal Law to Muslims.—

Notwithstanding any customs or usage to the

contrary, in all questions (save questions relating to

agricultural land) regarding intestate succession,

special property of females, including personal

property inherited or obtained under contract or gift

or any other provision of Personal Law, marriage,

dissolution of marriage, including talaq, ila, zihar,

lian, khula and mubaraat, maintenance, dower,

guardianship, gifts, trusts and trust properties, and

wakfs (other than charities and charitable

institutions and charitable and religious endowments) the rule of decision in cases where the parties are Muslims shall be Muslim Personal Law (Shariat).”

4. After the 1937 Act, in respect of the enumerated subjects under Section 2 regarding “marriage, dissolution of marriage, including talaq”, the law that is applicable to Muslims shall be only their Personal Law, namely, Shariat. Nothing more, nothing less. It is not a legislation regulating talaq. In contradistinction, the Dissolution of Muslim

Marriages Act, 1939 provides for the grounds for

dissolution of marriage. So is the case with the Hindu

Marriage Act, 1955. The 1937 Act simply makes Shariat applicable as the rule of decision in the matters enumerated in Section 2. Therefore, while talaq is governed by Shariat, the specific grounds and procedure for talaq have not been codified in the 1937 Act.”

13. In the light of the aforesaid, what emerges is that the parties are correct in urging that the dissolution of marriage by way of Mubaraat under the Muslim Personal Law is duly recognised as one of the modes of extra- judicial divorce. It is also evident that after the marriage between the parties is dissolved by way of Mubaraat, it is open for them to enter into an

agreement referred to as the ‘Mubaraat Agreement’ to record the factum of dissolution of their marriage through the mode of Mubaraat. However, this

agreement is only a private agreement between the parties and therefore, in case, the parties desire the factum of the dissolution of their marriage to be

recorded in a public document, it is always open to them to seek a declaration regarding the status of their marriage under Section 7(b) of the

Family Courts Act.

To read the judgment Kindly click here

Judgment Double Bench The Law Literates

All rights reserved (Adv Vaibhav Tomar)

The Supreme Court, while giving its verdict on the bulldozer action on Wednesday (November 13, 2024), has termed it completely wrong. The court says that until an accused is proven guilty, he is innocent and if his house is demolished during this time, it will be a punishment for the entire family.

The Supreme Court, while giving its verdict on the bulldozer action on Wednesday (November 13, 2024), has termed it completely wrong. The court says that until an accused is proven guilty, he is innocent and if his house is demolished during this time, it will be a punishment for the entire family.

The Supreme Court’s recent verdict highlights an essential aspect of justice: the presumption of innocence. The Court stated that until an accused is proven guilty, they remain innocent under the law. Therefore, demolishing an accused person’s property during an ongoing investigation would, in essence, punish not only the individual but their entire family—who may be uninvolved in the alleged crime. This judgment reinforces the principle that punishment cannot precede a fair and complete legal process, emphasizing the need for proportionality and caution in administrative actions.

to read the judgment click here!

Demolishment Supreme Court The Law Literates

all rights reserved (Vaibhav Tomar Adv)

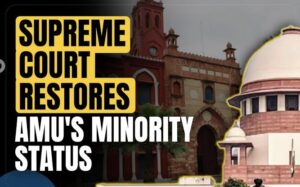

On Friday, a seven-judge Constitution bench of the Supreme Court reached a split decision (4:3) to overturn the landmark 1967 ruling regarding Aligarh Muslim University (AMU), which had previously deprived it of its minority status. This verdict marks a sea change, effectively undoing over five decades of legal standing.

Aligarh Muslim University:

Aligarh Muslim University remained a hot topic for a very long time. There were very distinguishing views of law literates in this topic. However, the Hon’ble Supreme Court has settled the dispute with a landmark Judgement. It is a judgement we should look forward to better describe Article 30:

“30. Right of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions.

(1) All minorities, whether based on religion or language, shall have the right to establish and administer educational institutions of their choice.

(1A) In making any law providing for the compulsory acquisition of any property of an educational institution established and administered by a minority, referred to in clause (1), the State shall ensure that the amount fixed by or determined under such law for the acquisition of such property is such

would not restrict or abrogate the rightguaranteed under that clause.

(2) The State shall not, in granting aid to educational institutions, discriminate against any educational institution on the ground that it is under the management of a minority,

Background and Brief Facts

In 1977, the Muhammadan Anglo-Oriental College was established in Aligarh. The college was a teaching institution affiliated to the Calcutta University at first and subsequently to the Allahabad University. The imperial legislature passed the Aligarh Muslim University Act 1920. The enactment, as the preamble indicates, “established and incorporated” Aligarh MuslimUniversity. The AMU Act was amended by the Aligarh Muslim University (Amendment) Act 1951 and Aligarh Muslim University (Amendment) Act 1965. The amendments related to the religious instructions of Muslim students and the administrative set-up of the university. Proceedings under Article 32 of theConstitution were instituted before this Court for challenging the constitutional validity of the 1951Amendment Act and the 1965 Amendment Act. A Constitution Bench in the decision in S Azeez Basha v.Union of India upheld the constitutional validity of the Amendments. The petitioners made a three-fold argument: (a) AMU was established by Muslims, who are a religious minority for the purposes of Article 30(1); (b) Article 30(1) guarantees Muslims the right to administer the University established by them; and (c) the 1951 and 1965 Amendments are violative of Article 30(1) to the extent that it infringed the right of the Muslim community to administer the institution. The amendments were also impugned on the ground that they violated Articles 14, 19, 25, 26, 29 and 31 of the Constitution.

The Union of India opposed the petitions, arguing that the Muslim minority did not have the right to administer AMU since they had not established the institution. It was submitted that AMU was established by Parliament. That being the case, it was contended that the amendments were not violative of Article 30(1).

A Constitution Bench dismissed the writ petitions in Azeez Basha (supra). The challenge on the ground of violation of Article 30(1) was rejected on the following grounds:

a. The phrase “establish and administer” in Article 30(1) must be read conjunctively. Religious minorities have the right to administer those educational institutions which they established. Religious minorities do not have the right to administer educational institutions which were not established by them, even if they were administering them for some reason before the commencement of the Constitution;

b. The word “establish” in Article 30(1) means “to bring into existence”;

c. AMU was not established by the Muslim minority for the following reasons:

i. AMU was brought into existence by the AMU Act, which was enacted by Parliament in 1920. Section 6 of the AMU Act provides that the degrees conferred to persons by the University would be recognised by the government. This provision indicates that AMU was established by the Government of India because the Muslim minority could not have insisted that the degrees conferred by a university established by it ought to be recognized by the Government. The AMU Act may have been passed as a result of the efforts of the Muslim community but that does not mean that AMU was established by them;

ii. The conversion of the College to the University was not by the Muslim minority but by virtue of the 1920 Act; and

iii. Section 4 of the AMU Act by which the MAO College and the Muslim University Association were dissolved, and the properties, rights and liabilities in the societies were vested in AMU shows that the previous bodies legally ceased to exist;

d. Since the Muslim community did not establish AMU, it cannot claim a right to administer it under Article 30(1). Thus, any amendment to the AMU Act would not be ultra vires Article 30 of the Constitution;

e. The argument that the administration of the University vested in the Muslim community though it was not established by them was rejected. The administration of AMU did not vest in the Muslim minority under the AMU Act for the following reasons:

i. Although all the members of the Court (which was the supreme governing body in terms of Section 23 of the AMU Act) were required to be Muslims, the electorate (which elected the members

of the Court) did not comprise exclusively of Muslims;

ii. Other authorities of AMU such as the Executive Council and the Academic Council were tasked with the administration of the University and were given significant powers. The members of these bodies were not required to be Muslims;

iii. The Governor General (who was the Lord Rector) was also entrusted with certain “overriding” powers concerning the administration of the University. The Governor General was not required to be a Muslim. In terms of Section 28(3), the Governor General had overriding powers to amend or repeal the Statutes. The Governor General possessed similar powers with respect to amending or repealing Ordinances. In terms of Section 40, the Governor General had the power to remove any difficulty in the establishment of the University; and

iv. The Visiting Board which consisted of the Governor of the United Provinces, the members of the Executive Council and Ministers were not necessarily required to be Muslims;

f. The term “establish and maintain” in Article 26 must be read conjunctively, like the phrase “establish and administer” in Article 30. Assuming that educational institutions fall within the ambit of Article 26, the Muslim community does not have the right to maintain AMU because it did not establish it; and

g. The impugned amendments do not violate Articles 14, 19, 25, 29 and 31.

In 1981, a two-Judge Bench of this Court in Anjuman-e-Rahmaniya v. District Inspector of Schools was faced with a question of whether V.M.H.S Rehmania Inter College is a minority educational institution. By an order dated 26 November 1981, the Bench questioned the correctness of Azeez Basha (supra) and referred the matter to a Bench of seven Judges, in the following terms:

“After hearing counsel for the Parties, we are clearly of the opinion that this case involves two substantial questions regarding the interpretation of Article 30(1) of the Constitution of India. The present institution was founded in the year 1938 and registered under the Societies Registration Act in the year 1940. The documents relating to the time when the institution was founded clearly shows that while the institution was established mainly by the Muslim community but there were members from the non-Muslim community also who participated in the establishment process. The point that arises is as to whether Art. 30(1) of the Constitution envisages an institution which is established by minorities alone without the participation for the factum of establishment from any other community. On this point, there is no clear decision of this court. There are some observations in S. Azeez Basha & ors. Vs. Union of India 1968(1) SCR 333, but these observations can be explained away. Another point that arises is whether soon after the establishment of the institution if it is registered as a Society under the Society Registration Act, its status as a minority institution changes in view of the broad principles laid down in S. Azeez Basha’s case. Even as it is several jurists including Mr. Seervai have expressed about the correctness of the decision of this court in S. Azeez Basha’s case. Since the point has arisen in this case we think that this is a proper occasion when a larger bench can consider the entire aspect fully. We, 8 W.P.(C) No. 54-57 of 1981 therefore, direct that this case may be placed before Hon. The Chief Justice for being heard by a bench of at least 7 judges so that S. Azeez Basha’s case may also be considered and the points that arise in this case directly as to the essential conditions or ingredients of the minority institution may also be decided once for all. A large number of jurists including Mr. Seervai, learned counsel for the petitioners Mr. Garg and learned counsel for respondents and interveners Mr. Dikshit and Kaskar have stated that this case requires reconsideration. In view of the urgency it is necessary that the matter should be decided as early as possible we give liberty to the counsel for parties to mention the matter before Chief Justice.”

The judgement in appeal by a Division Bench of the Allahabad High Court was reported as Aligarh Muslim University v. Malay Shukla. The Division Bench affirmed the judgment of the Single Judge, with some modifications. AN Ray, C.J. speaking for the Division Bench held that:

a. When the minority status is not assumed or admitted, the factor of administration and control by non-minority groups becomes important. The indicia for the determination of whether an educational institution is a minority educational institution is (i) who established it; (ii) who is responsible for administration; and (iii) the purpose of the establishment;

b. By amending Section 2(l), Parliament attempted to overrule the decision in Azeez Basha (supra). This amendment does not change the basis of that decision because the incorporation of the University was not the sole factor which influenced the decision;

c. Section 5(2)(c) is discriminatory. Further, it does not change the basis of the decision in Azeez Basha (supra);

d. The removal of the words “establish and” from the long title and preamble of the AMU Act is impermissible because Azeez Basha (supra) held that incorporation and establishment are intimately connected. Permitting the omission of the word “establish” may give rise to doubts as to whether incorporation alone is sufficient for the surrender of the minority character of the institution;

e. AMU is not merely a university but a field of legislative power in Entry 63 of List I of the Seventh Schedule to the Constitution. Section 2(l) modified the definition of a word in an entry in the Seventh Schedule. The definition of a word in the Constitution cannot be altered except through a constitutional amendment. The AMU (Amendment) Act 1981 therefore suffers from lack of legislative competence; and

f. Parliament lacks the authority to create a minority institution. Only a minority can do so and courts may declare whether a minority hassucceeded in establishing an institution under Article 30.

Conclusions

In view of the above discussion, the following are our conclusions:

a. The reference in Anjuman-e-Rahmaniya (supra) of the correctness of the decision in Azeez Basha (supra) was valid. The reference was within the parameters laid down in Central Board of Dawoodi Bohra Community ;

b. Article 30(1) can be classified as both an anti-discrimination provision and a special rights provision. A legislation or an executive action which discriminates against religious or linguistic minorities in establishing or administering educational institutions is ultra vires Article 30(1). This is the anti-discrimination reading of the provision. Additionally, a linguistic or religious minority which has established an educational institution receives the guarantee of greater autonomy in administration. This is the ‘special rights’ reading of the provision;

c. Religious or linguistic minorities must prove that they established the educational institution for the community to be a minority educational institution for the purposes of Article 30(1);

d. The right guaranteed by Article 30(1) is applicable to universities established before the commencement of the Constitution;

e. The right under Article 30(1) is guaranteed to minorities as defined upon the commencement of the Constitution. A different right-bearing group cannot be identified for institutions established before the adoption of the Constitution;

f. The incorporation of the University would not ipso facto lead to surrendering of the minority character of the institution. The circumstances surrounding the conversion of a teaching college to a teaching university must be viewed to identify if the minority character of the institution was surrendered upon the conversion. The Court may on a holistic reading of the statutory provisions relating to the administrative set-up of the educational institution deduce if the minority character or the purpose of establishment was relinquished upon incorporation; and

g. The following are the factors which must be used to determine if a minority ‘established’ an educational institution:

i. The indicia of ideation, purpose and implementation must be satisfied. First, the idea for establishing an educational institution must have stemmed from a person or group belonging to the minority community; second, the educational institution must be established predominantly for the benefit of the minority community; and third, steps for the implementation of the idea must have been taken by the member(s) of the minority community; and

ii. The administrative-set up of the educational institution must elucidate and affirm (I) the minority character of the educational institution; and (II) that it was established to protect and promote the interests of the minority community.

The view taken in Azeez Basha (supra) that an educational institution is not established by a minority if it derives its legal character through a statute, is overruled. The questions referred are answered in the above terms. The question of whether AMU is a minority educational institution must be decided based on the principles laid down in this judgment. The papers of this batch of cases shall be placed before the regular bench for deciding whether AMU is a minority educational institution and for the adjudication of the appeal from the decision of the Allahabad High Court in Malay Shukla (supra) after receiving instructions from the Chief Justice of India on the administrative side.

In the end the supreme court seven-judge Bench in 4:3 majority judgment says that’s recognition by law won’t annul minority status. Further, court returns case to a regular Bench to examine the question of the university’s minority status.

To read the judgment kindly click here

AMU Judgment (Aligarh Muslim University Versus Naresh Agarwal & Ors) The Law Literates

All rights reserved (Adv Vaibhav Tomar)

Dowry death – Aggrieved by the judgment of conviction convicting the appellants finding them guilty under Sections 304B/34 and 498A/34 IPC- The Law Literates

PARAMJIT vs STATE OF DELHI CRLA 566/01 12/05/17 [ DELHI HIGH COURT]

Dowry death – Aggrieved by the judgment of conviction convicting the appellants finding them guilty under Sections 304B/34 and 498A/34 IPC and order on sentence vide which the appellants were sentenced to undergo seven years rigorous imprisonment for the offence under Section 304B/34 IPC – The scope of convicting an accused under Section 302 IPC i.e. for commission of murder and Section 304B IPC i.e. dowry death are altogether different. The ingredients of both these Sections are also separate.

In convicting an accused under Section 302 IPC, the prosecution is bound to prove its case either by way of direct evidence or with the connecting chain of circumstances, whereas convicting an accused for commission of dowry death specific circumstances are to be established. In the present case, since co-convict has already been convicted under Section 302 IPC by treating the death of deceased as murder, no case is made out against the appellants to convict them under commission of dowry death of the deceased.

To read the judgment Click here

PARAMJIT KAUR & Mangat Singh V:s State The Law Literates Judgment

All Rights Reserved (Adv Vaibhav Tomar)

Appeal Allowed – Hindu Marriage Act Section 13(1)(i-a)Family Courts ActSection 19 Ex-parte divorce—Mental and physical cruelty by wifeDismissal of suit by Family Court.

Jitendra kumar Shrivastava vs Sweta Shrivastava FA 32/23 22/07/24 [ ALLAHABAD HIGH COURT ]

Hindu Marriage Act Section 13(1)(i-a)Family Courts ActSection 19 Ex-parte divorce—Mental and physical cruelty by wifeDismissal of suit by Family Court—Appeal against —The husband alleged harassment by the wife, including abusive behavior, public insults, damage to property, and threats of false criminal casesThe wife forced the husband fo live in a separate room, depriving him of cohabitation, which constitutes mental and physical crueltyThe Family Court erred in disregarding the testimony of the husband’s father, as family members are natural witnesses to incidents occurring within the home—The husband’s father’s testimony, as a natural witness, cannot be arbitrarily dismissedThe wife’s refusal to cohabit amounts to physical and mental cruelty, impacting the husband’s wellbeing—Divorce decree granted in favor of the husband Appeal allowed.

Relevant Paras

Although the ground of the plaintiff’s desertion by the defendant is also established from the material available on record, since the Family Court did not frame any issue on this point, and the ground of cruelty alone is sufficient for allowing the appeal, there is no need go into this question in this appeal. In view of the aforesaid discussion, we answer the points involved in this appeal as follows: –

a) There was sufficient evidence to prove the ground of cruelty pleaded by the plaintiff-appellant for grant of a decree of divorce.

b) The judgment and decree of dismissal of suit passed by the Family Court is unsustainable in law.

To read the Judgment click here!

Jitender kumar vs Shweta Shrivastva appeal allowed The Law Literates

All Rights Reserved (Adv Vaibhav Tomar)

Sections 498-A and 306 IPC Appellant was convicted for for allegedly ill-treating his wife leading her to commit suicide by immolatio- Appellant was acquitted, and the conviction was quashed

Sections 498-A and 306 IPC Appellant was convicted for for allegedly ill-treating his wife leading her to commit suicide by immolation The correctness of the conviction based on the evidence, including multiple dying declarations and the alleged illtreatment — Appellant argued that the argued that the prosecution failed to prove the charges, highlighting inconsistencies in the dying declarations and questioning the fitness of the deceased to give statements — The prosecution maintained that the dying declarations were consistent and that the ill-treatment by the husband led to the suicide —The court acquitted appellant, setting aside the conviction due to inconsistencies in the dying declarations and lack of evidence proving the charges beyond a reasonable doubt —The court found significant inconsistencies in the dying declarations and noted the absence of certification of the deceased’s fitness to give statements —The court emphasized the need for clear evidence of abetment and mental cruelty to sustain a conviction under Sections 498-A and 306 of the IPC — Appellant was acquitted, and the conviction was quashed due to insufficient evidence and procedural lapses in recording the dying declarations.

Ejaz vs State of Maharashtra CRLA 289/02 10/09/24 [ BOMBAY HIGH COURT ]

Specific Relief Act Sections 20 and 16 (c) Specific performance Agreement to sell Readiness and willingness – Agreement was executed by plaintiff and he filed the suit, but before he could be examined, in the court he expired

RADHESHYAM vs BHERU FA 197/20 11/03/24 [ MADHYA PRADESH HIGH COURT ]

Specific Relief Act Sections 20 and 16 (c) Specific performance Agreement to sell Readiness and willingness – Agreement was executed by plaintiff and he filed the suit, but before he could be examined, in the court he expired – His second son entered into witness box as PW-1 – He gave the evidence only on the basis of the contents of the agreement to sell – According to him, he was not present at the time of signing of the agreement or extension of the time – Therefore, his depositions in respect of the agreement to sell or extension of time or socalled refusal by defendant No.1 for execution of the sale deed, are not based on his personal knowledge – He cannot give evidence to establish the readiness and willingness of the purchaser i.e. original the plaintiff.

Relevant Paras:

34. The agreement was executed by plaintiff Radheshyam and he filed the suit,

but before he could be examined, in the court he expired. His second son Pradeep

Mehta entered into witness box as PW-1. He gave the evidence only on the basis of the contents of the agreement to sell. According to him, he was not present at the time of signing of the agreement or extension of the time. Therefore, his depositions in respect of the agreement to sell or extension of time or so-calledrefusal by defendant No.1 for execution of the sale deed, are not based on his personal knowledge. Therefore, he cannot give evidence to establish the readiness and willingness of the purchaser i.e. original the plaintiff. He admitted in para 9 of the cross-examination that Bheru Singh was in need of money, therefore, he agreed to sell the house to the plaintiff and the time was fixed for payment of the

remaining amount of sale consideration and the sale deed was not executed within that agreed time and the time was extended because of death in the family of Bheru Singh. There are certain fact which are in the knowledge of the party which can be proved by him only by entering into witness box especially in facts related to readiness and willingness. A party can appear only as a witness in his personal capacity and whatever knowledge he has about the case he can state on oath, no one can appear as a witness on behalf of the party in the capacity of that party. In

the case of Janki Vashdeo Bhojwani v. Indusind Bank Ltd., reported in (2005) 2 SCC 217:-

“14. Having regard to the directions in the order of remand by which this Court placed the burden of proving on the appellants that they have a share

in the property, it was obligatory on the part of the appellants to have entered the box and discharged the burden. Instead, they allowed Mr Bho-

jwani to represent them and the Tribunal erred in allowing the power-of-at- holder to enter the box and depose instead of the appellants. Thus, the appellants have failed to establish that they have any independent source of income and they had contributed for the purchase of the property

from their own independent income. We accordingly hold that the Tribunal has erred in holding that they have a share and are co-owners of the prop-

erty in question. The finding recorded by the Tribunal in this respect is set aside.

15. Apart from what has been stated, this Court in the case of Vidhyadhar v. Manikrao [(1999) 3 SCC 573] observed at SCC pp. 583-84, para 17 that:

“17. Where a party to the suit does not appear in the witness box and states his own case on oath and does not offer himself to be cross-examined by the

other side, a presumption would arise that the case set up by him is not cor- rect….”

16. In civil dispute the conduct of the parties is material. The appellants have not approached the Court with clean hands. From the conduct of the

parties it is apparent that it was a ploy to salvage the property from sale in the execution of decree.

17. On the question of power of attorney, the High Courts have divergent views. In the case of Shambhu Dutt Shastri v. State of Rajasthan [(1986) 2

WLN 713 (Raj)] it was held that a general power-of-attorney holder can ap pear, plead and act on behalf of the party but he cannot become a witness

on behalf of the party. He can only appear in his own capacity. No one can delegate the power to appear in the witness box on behalf of himself. To

appear in a witness box is altogether a different act. A general power-of-at- holder cannot be allowed to appear as a witness on behalf of the

plaintiff in the capacity of the plaintiff.

To read the judgment click here

Radhe shyaam ve bheru singh MP High Court The Law literates

all rights reserved (Àdv Vaibhav Tomar)