Registered But Not Owned? The Supreme Court Just Redefined Property Ownership in India

Registered But Not Owned? The Supreme Court Just Redefined Property Ownership in India

Introduction: The Illusion of Ownership

In India, owning property has always been seen as a symbol of security, success, and stability. Families invest their life savings, sign off on long and expensive sale agreements, and finally breathe a sigh of relief once their property is registered. That moment, when the registrar stamps the sale deed, feels like the finish line.

But what if I told you that having a registered deed does not actually make you the owner? Sounds shocking, right? Yet, that is exactly what the Supreme Court of India has clarified in a game-changing verdict in 2025 and as a practicing lawyer, I believe this may be one of the most important reminders in decades about the legal meaning of ownership.

The Case That Sparked It All

The matter before the court wasn’t new. A cooperative society had sold parcels of land to various individuals through registered sale deeds. The buyers, relying on those documents, believed they had legally become the owners. Their names were on papers, the registration was complete what could possibly go wrong?

Plenty, as it turned out.

The society that executed those transfers did not have a clean title to begin with. It never lawfully acquired the land, and there was no proper chain of title. The purchasers had the form the registration but not the substance: no valid origin of ownership, and no legitimate possession. The issue reached the doors of the apex court, and what followed was a ruling that turned conventional understanding on its head.

What the Supreme Court Held

In its verdict, the Supreme Court ruled in no uncertain terms that registration of a property document does not by itself confer ownership. The act of registering a sale deed or agreement is merely a procedural requirement under the Registration Act of 1908. It creates public notice and admissibility in evidence, but not title in itself.

Ownership, the Court emphasised, is a legal status that arises only when the transferor has a valid title to the property and has lawfully delivered possession to the transferee. Without this, a registered document becomes just a piece of paper legally ineffective and incapable of standing up in court.

This clarity is crucial. It distinguishes between registration as a legal formality and title as a substantive legal right. The Court further noted that even the most perfectly drafted and duly stamped deed cannot create rights if the person executing it had no rights to begin with.

Possession: The Silent Hero

Another vital aspect the Court emphasised was the role of possession in determining ownership. In Indian property law, possession isn’t just a physical fact it often carries presumptive legal weight. If a person has been in long, undisputed possession, especially with the knowledge of others, it can even help establish ownership over time (though that’s another discussion involving adverse possession).

But in this case, possession was never properly transferred. The so-called owners had documents, but not the land. And once again, the Court held firm: without lawful possession, ownership is incomplete even if the documents are registered.

Why This Judgment Is a Big Deal

This ruling has far-reaching consequences. For decades, Indian property transactions have operated on the assumption that once a property is registered in someone’s name, they become the owner. For many laypersons and even some practitioners “registry ho gaya” was the end of the story. But legally, this was never the whole truth.

Before this judgment, while courts did expect proof of title and possession, it was rare for ownership to be outright rejected just because the original seller didn’t have a perfect title, especially when registration had taken place. This verdict decisively changes that. It reasserts the need for a valid origin of title, a clear chain of transfer, and actual delivery of possession not just a rubber stamp from the registrar.

How the Law Stood Before — And What’s Changed

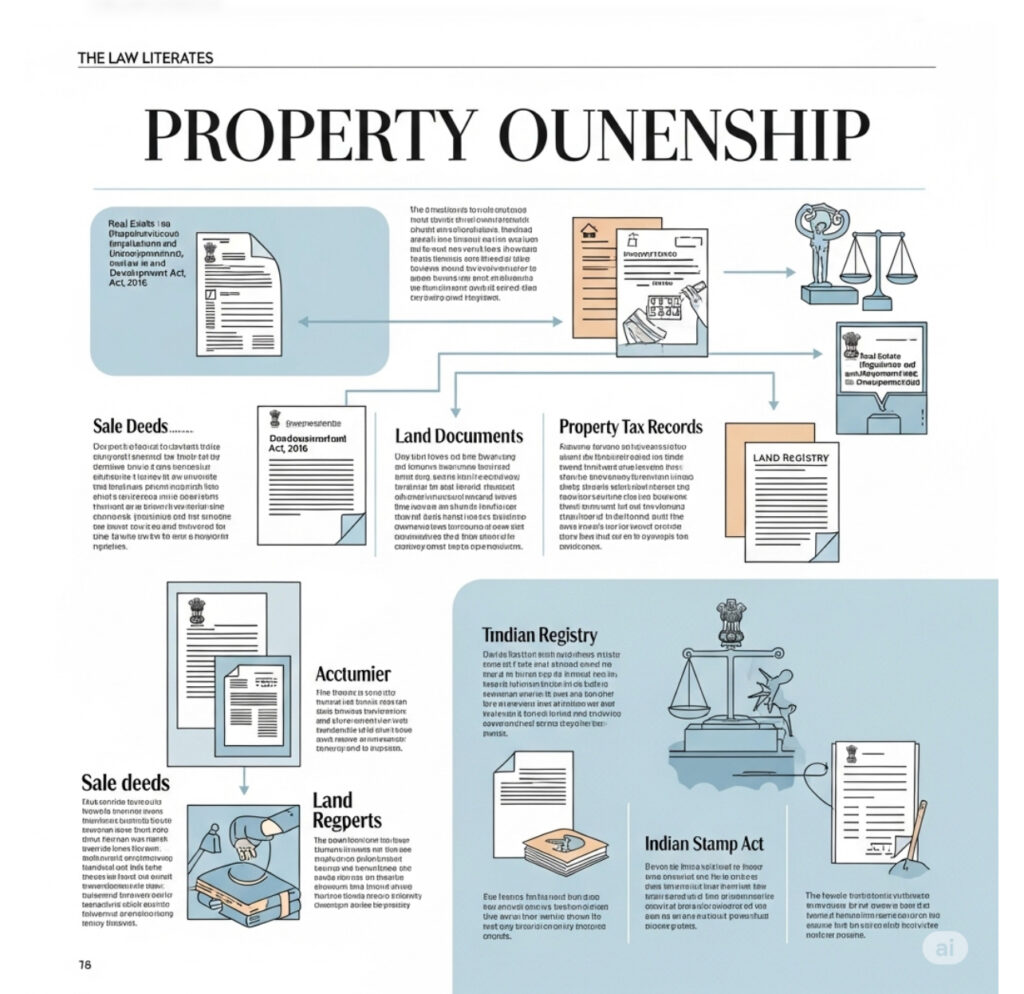

Historically, ownership in India was determined by a bundle of rights: title, possession, and the ability to transfer or alienate the property. Registration was always part of the legal process, but never a complete proof in itself. However, over time, due to the complexity of land records, delays in litigation, and lack of awareness, registration began to be treated as proof of ownership in practice, if not in law.

This judgment re-aligns that practice with legal reality. It reminds everyone from buyers to brokers to bankers that a registered document cannot transfer what never legally existed. The principle of nemo dat quod non habet (no one can transfer what they do not own) is alive and well in Indian jurisprudence.

What It Means for Buyers and Sellers

For buyers, this verdict should sound a warning bell. Before signing that sale deed or transferring funds, it is no longer enough to see a registered document or trust the word of the developer. Buyers must conduct thorough due diligence verify the root of title, examine past transactions, check mutation records, confirm physical possession, and obtain a non-encumbrance certificate. It’s no longer just good practice it’s essential.

For sellers, this judgment calls for honesty and caution. One cannot simply execute a sale deed and hope that registration will mask flaws in their title. If the ownership is unclear, disputed, or under litigation, those facts must be disclosed. Failing to do so could invalidate the entire transaction.

For us, as legal professionals, this judgment is a moment of both caution and opportunity. It raises the bar for legal scrutiny in property transactions. Drafting a good sale deed is no longer enough lawyers must now investigate title, examine possession, and advise clients on real risks.

At the same time, it offers us a chance to reinforce the value of the legal profession in real estate matters. In a field riddled with informal dealings and half-baked documentation, this verdict tells the world: law matters, and you better follow it properly.

Conclusion: More Than a Judgment — A Reset Button

This Supreme Court ruling does not merely interpret a statute it resets the way India views property ownership. It restores faith in legal principles, protects genuine owners, and warns against shortcuts and legal illusions.

As a lawyer, I welcome this decision. It brings clarity in a field that was becoming increasingly murky. It strengthens the rule of law in real estate, where ambiguity often leads to fraud and long-drawn disputes. And most importantly, it reminds everyone whether they’re buying a flat or a farm that ownership is not a matter of paperwork alone. It is a matter of law, possession, and truth.

So next time someone waves a registered deed and says, “This land is mine,” ask them:

“But did you check the title?”

All Rights Reserved (Vaibhav Tomar Adv)

MERTHYTJTJ932708MARETRYTR

В основе нашей успешной работы, лежит предельное внимание к каждой мелочи, учёт индивидуальных особенностей двигателя, глубокие знания и большой практический опыт http://dmalmotors.ru/

Если раньше мотор автомобиля можно было починить подручными средствами, то сегодня, для этого необходимы специальные знания и высокоточное оборудование http://dmalmotors.ru/zamena-i-remont-stsepleniya.html

После полной разборки и очистки ДВС проводится его дефектовка, то есть специалисты определяют степень износа отдельных элементов, проверяют БЦ и ГБЦ на предмет наличия трещин и других дефектов, промеряют цилиндры, измеряют зазоры, оценивают выработку и т http://dmalmotors.ru/component/content/article/9-aktsii2/24-diagnostika-khodovoj-besplatno2.html?Itemid=101

д http://dmalmotors.ru/zamena-masel-i-filtrov.html

Конечной целью является оценка состояния и замер всех сопряженных и других элементов, после чего осуществляется сравнение имеющихся размеров с заводскими допусками http://dmalmotors.ru/zamena-masel-i-filtrov.html

Можно отметить, что двигатель оснащен подогревом воздуха при холодном запуске от электрического факела http://dmalmotors.ru/remont-starterov/2-uncategorised/25-aktsiya.html

А система охлаждения не только использует антифриз, но и оснащена автоматической системой регулирования http://dmalmotors.ru/promyvka-inzhektorov.html

Автомат газированной воды АГВ-Н-50П https://vendavtomat.ru/zhevatelnaya_rezinka/napolnitel_mekhanicheskih_avtomatov/konfety/juice_tutti_frutti

Конструкция автоматов газводы постоянно совершенствуется в направлении повышения их надежности, долговечности и расширения их функциональных возможностей https://vendavtomat.ru/napolnitel_mekhanicheskih_avtomatov/igrushki_dlya_kapsul_28_34_mm/myach_futbolnyj

• Выдача охлажденной воды https://vendavtomat.ru/zapasnye_chasti_i_raskhodniki_dlya_torgovyh_avtomatov/zapchasti-i-raskhodniki-dlya-pitevyh-fontanov

* Цена за 1 упаковку https://vendavtomat.ru/napolnitel_mekhanicheskih_avtomatov/igrushki_v_kapsule_28mm_34mm/slajm_k28

Гарантия качества https://vendavtomat.ru/igrushki_dlya_kapsul_28_34_mm/myach_futbolnyj

У нас многолетний опыт производства и продаж автоматов-сатураторов газированной воды в России и странах СНГ Мы предлагаем широкий ассортимент популярных моделей автоматов газированной воды с разной производительностью Мы являемся производителем натуральных сиропов ГОСТ 28188-89 для АГВ Наши инженеры сервисного центра – это команда профессионалов с многолетним опытом , которые способны в любой момент, как на месте, так и дистанционно, устранить любые неисправности автомата Являясь производителями, мы минуем посредников, поэтому готовы предложить самые низкие цены на оборудование , при неизменном высоком качестве выпускаемой продукции Продукция предприятия всегда в наличии , даже в разгар «питьевого» сезона За каждым предприятием-партнером мы закрепляем ведущего специалиста отдела сбыта и инженера , которые незамедлительно и профессионально проконсультируют и решит любую Вашу проблему https://vendavtomat.ru/index.php?route=product/manufacturer/info&manufacturer_id=37